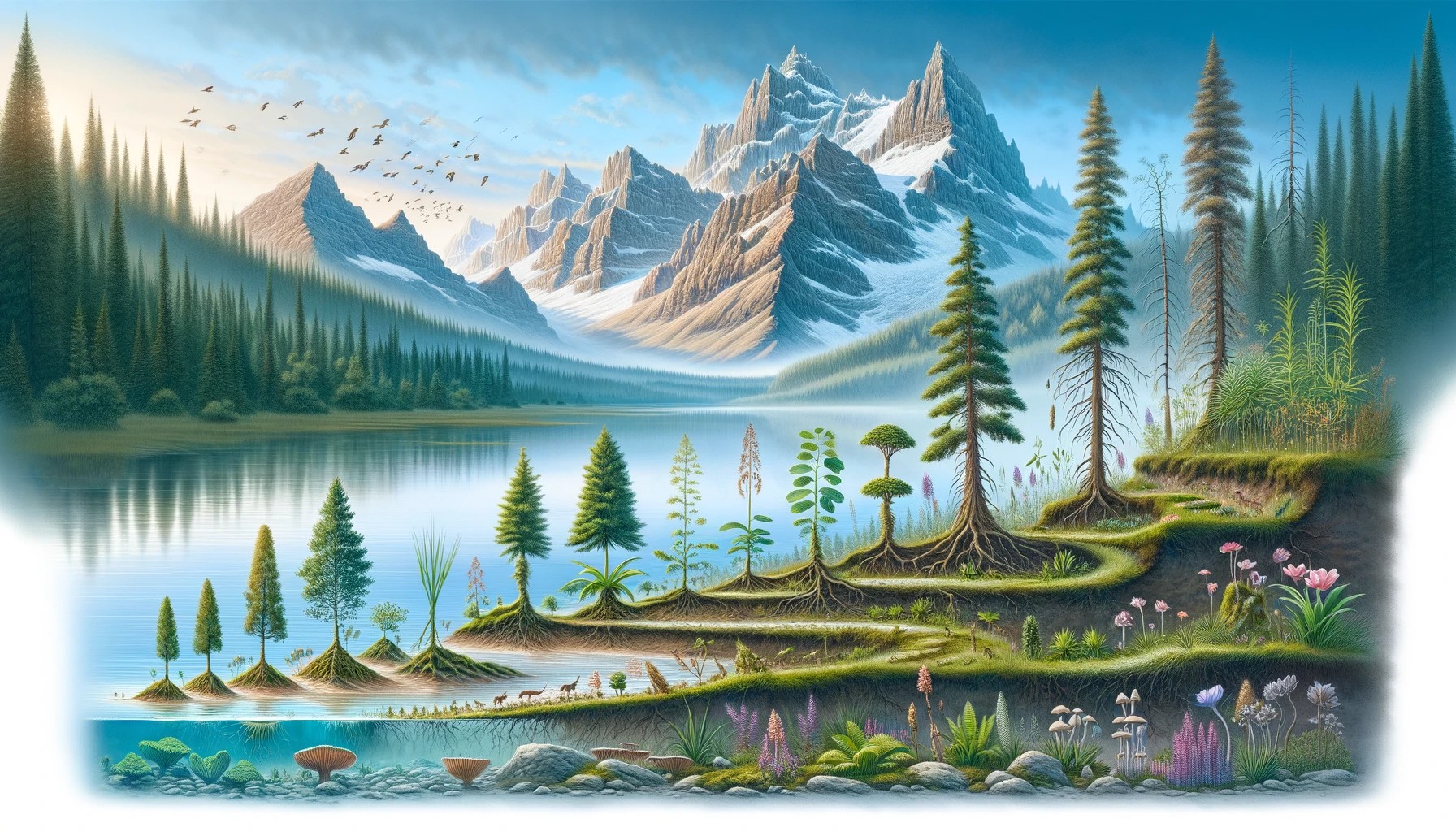

The only way early plants could become more competitive was to get bigger, taller, and move up into the unimpeded sunshine where photosynthesis could be as efficient as possible. More photosynthesis, more sugar, more energy, better life. Two amazing molecules facilitated the whole journey: cellulose and lignin, the cell wall reinforcers. These molecules, along with the development of more efficient root systems, allowed plants to leave the steady guaranteed water supply of seashore, creekside, and lakeside, and they would begin their incredible journeys to the farthest ends of the earth—from high in the mountains, north and south to the edges of the polar ice caps and everywhere in between. The planet is 70% blue—the oceans—and nearly 30% green, except, of course for the world’s deserts. Today nearly 400,000 species of all types of plants are known, with, no doubt, more discoveries to come. It seems plants like it here.

Early plants were small by today’s standards; the first early plants were basically flat upon the land. Then, as some evolutionary developments began, other types appeared, many larger than their early relatives. Those early relatives are still with us; they are called bryophytes, mosses, hornworts and liverworts. These early plants do not have the vascular plumbing, or the root systems, of most other larger plants, which are called the tracheophytes. The root words of these two terms are moss plant for the bryophytes and trachea plant for the tracheophytes. Spending some time on the forest floor with these ancient beings is like time travel to deep in the past, well before the large trees that now surround them developed. This attests to their survival skills; you have to have your chops down pretty good to survive unchanged for over 400 million years.

Most smaller plants (not trees and shrubs) exhibit one growth method called primary growth—primary being first, or shoot growth. Woody plants also have primary growth, but additionally exhibit secondary growth, which allows the stem to increase in width and strength. Both primary and secondary growth occur in zones called meristems, which are tissue zones that exhibit cells that are called initials, and their derivatives, mother cells and daughter cells. Meristems have the ability to produce new cells, new growth, either annually or overextended periods of time. The meristems for primary growth, the lengthening of shoot and root tips, only function during one growing season. The next year, the new bud that formed at the shoot tip will take up the task for the next year. The root tip functions in a similar way. The shoot apical meristem is called the SAM; the root apical meristem is called the RAM. The meristems responsible for secondary growth are called the vascular cambium and the cork cambium. The vascular cambium (VC) grows nearly the entire growth and bulk of the trunk, whereas the cork cambium (CC) grows the outer bark layer. The CC is produced annually. The VC lasts as long as the tree, sometimes thousands of years.

Let’s think about shoot growth (primary growth) for a minute. At the overwintering shoot tip is the terminal bud. It was the last bud on the shoot formed in the previous year’s growth. During the previous year as the shoot continued to grow, it kept expanding from the tip, pushing the SAM outward, the latest newly-forming cells just behind it. As it does so, it also generates the nodes or buds that later form into side shoots. These have three patterns along the new stem, either singly (alternate), in pairs (opposite) or in groups (whorls). Look closely and you can prove this for yourself.

Let’s imagine a point during the first growth flush that is usually ongoing sometime in June. Take ahold of the new shoot; you can follow it back towards the trunk to its bud scar. The bud scar is a tiny ring of tissue all around the shoot in the bark that marks the transition to this year’s growth from last year’s growth. It is the site where the last overwintering terminal bud was, the bud that became this shoot. When that bud started growing (broke) it began to grow the shoot we are looking at. As you inspect this year’s shoot you will see that the oldest newly formed side buds are closest to the bud scar. The farther you move out to the tip, the smaller and less developed the side buds are. If there is a newest, last formed bud at or close to the tip, it will be the smallest, least formed, most immature of all the buds along the stem. This is because it is the youngest bud on the shoot, meaning it was formed last, meaning that the shoot constantly expands from the SAM right at its tip. The new shoot tissue forms behind it. Cool, eh? Bud scar identification is a tool you need to learn. It is the first thing I look at when approaching a new tree—how are you growing? How are you doing? Do they treat you well here? I stand way back to look up to the tops of spruce trees where I can see the latest shoot extensions, to gauge the growth rate and overall health of the tree.