The hawthorns are a much larger group of small trees than we may realize, with over 30 species native in Canada. They form small trees growing into thickets in the wild. There used to be more varieties available but the market has gone in such a way that now the two from Morden, the Toba and the Snowbird, are dominating. The Toba is pink flowering and the Snowbird is white.

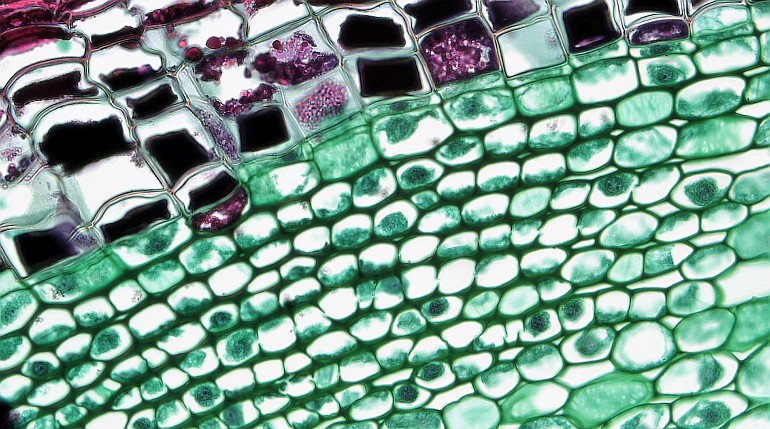

They are quite susceptible to fire blight and cedar/apple rust, so require constant weekly inspection.This rust called gymnosporangium is worth some further reading. It's a rust that uses junipers as the alternative host, with a complex interesting life cycle.

Native species that are good are the Black, Fireberry and Columbia. If you can find them. the Fleshy, Russian and Oneseed are also good cultivated varieties.

Anyone who has a pink flowering Toba or its sister tree, the white flowering Snowbird, will know after a few years what a tangle these trees can become. The reason is that they sucker readily in the crown, even as young plantings. Just a few years later, the shoots or suckers have become so tangled and integral to the tree’s form that most of us are afraid to touch it for fear of harm.

The suckers tend to grow a little faster than the other branches and, therefore, establish spaces within the crown for themselves early on. It seems like it would be detrimental to remove them. Usually when I prune Hawthorns, I end up leaving some of the suckers, which have now become branches, because to remove them would damage the overall balanced look.

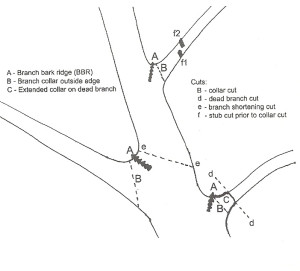

If you have a hard and fast rule about removing hawthorn suckers, then you do so to the plant's detriment. What hawthorns want us to do is to use our artist’s eye. I mean specifically being able to look at a tree, or sections of a tree, and in your mind make certain branches disappear. No magic wand required here, just practice. I will assume that we are talking about healthy branches and that the dead have already been removed.

Here's How I Do It:

1) Take a look, scan through the section in question. Say there are two options here. Make one of them invisible. How? Don’t focus on it, don’t look directly at it; look through, beside, behind at the the other option.

2) How does it look? Look again. Now switch back. Make the other option invisible. Imagine one choice is green and the other blue. Look and see only the green choice, now only the blue.

3) Which do you like better? Look twice, because once you cut you can’t go back.

When I am pruning a tree this difficult, I stand back and look a lot. I walk around the tree, scanning back and forth, up and down. I pruned a twenty-some-year-old Toba in Varsity last year that was a real challenge. It had never been touched. I took my time and looked a lot. There were lots of options. I decided to prune the tree in phases. First, I removed all the small extraneous suckers and deadwood; this cleaned up the visual lines, making it easier to see. I then started considering the options. It turned out that in several areas of the tree, the best choice was leaving an old sucker that had made its way and its own space in the crown. Many times, this was the best choice overall.

Near these shoots, I thinned slower-growing branches to make room for the sucker. This is a set of ideas that work for a complex pruning challenge.

Note, hawthorns are quite susceptible to fire blight .If green leaves suddenly turn a rusty red and shrivel up, there is a good chance your tree has been infected.

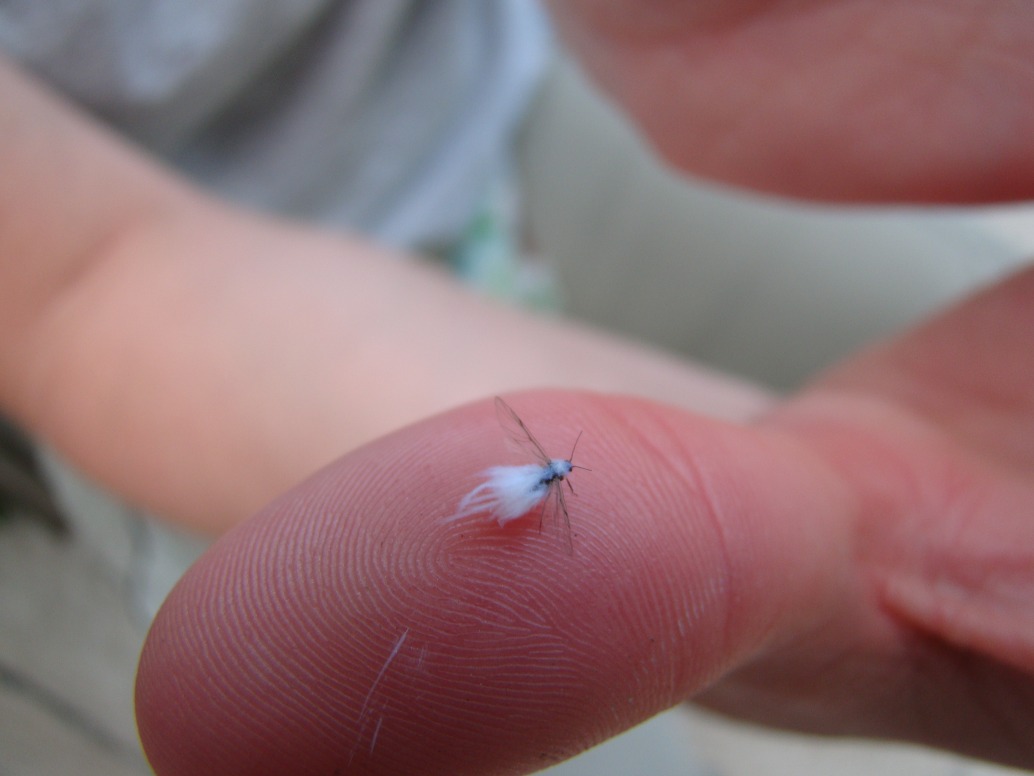

Hawthorns are also susceptible to hawthorn/juniper rust. Look for strange whitish/orange hairy looking bumps on leaves. These bumps can be a centimeter in size. The other player in this situation is junipers, the rust's alternative host. Look for woody galls inside your junipers; in early summer the galls will grow brown jelly looking like growth. These, the telia, are producing spores. Best to keep infected trees well watered; healthy trees with strong immune systems can fight the disease much better than a drought-stricken tree.