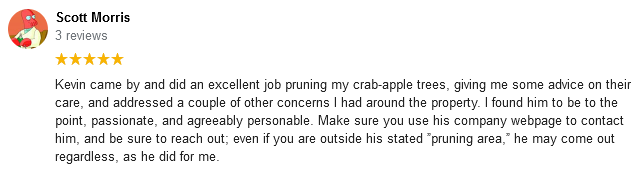

(Continued from A Year in the Life of Your Tree - 7)

Fall/Autumn

Another year's growing season is close to its end. Fruit and seeds are mature, apples soon to be picked. Last night's frost has left a crisp clarity to the garden There is a hint of wood smoke. The leaves, many with tears, holes and hollows, have worked hard all season, and are about done. Chewed by insects, torn by hail, infected with fungal leaf spots and discoloration from aphid feeding, these remarkably tough little engines of the tree have endurance beyond our reckoning.

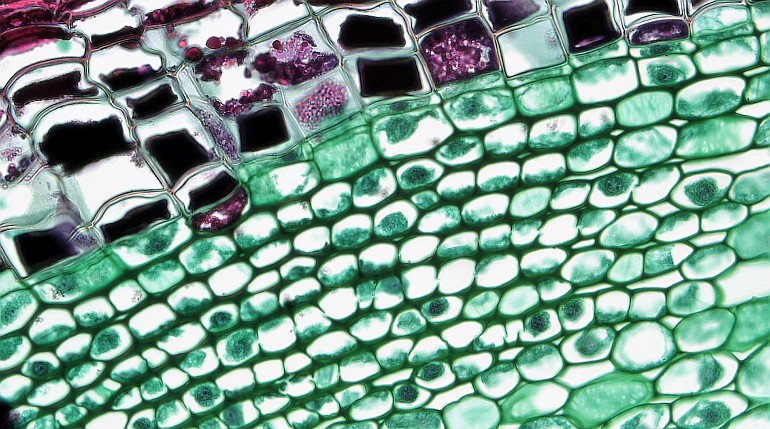

Now with the shorter days and less light the leaves feel what is to come. The green chlorophyll is fading, certainly a loss for the tree, but the palette about to appear marks for most people a favorite season. As long as we don't get a killing frost the rainbow colors of the leaves will be revealed. Many of the pigments we associate with fall colors have been present in the leaves all along, but green is king and these other colors are not seen until the chlorophyll steps down.

Rare it is to get through autumn without a hard frost killing the leaves of some trees, but when we do get a slow lingering fall it is a marvellous sight. American mountain ash in their last phase go from a deep red into a purple. Here in zone 3, without the powerful maple show, some of these other trees are doing a pretty good job. The other ash, very frost sensitive, can produce a bright lemon yellow that glows in sunlight.

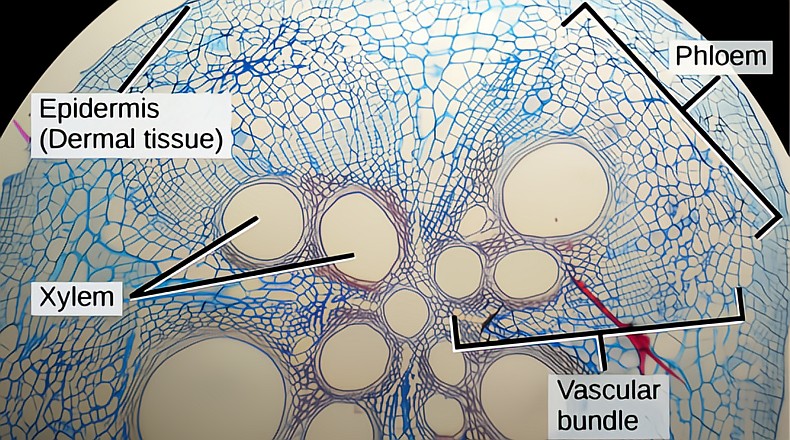

If we do get a killing frost before the leaves are finished and naturally removed, they will persist, sometimes into the next year, depending on the strength of the stem and attachment. Indeed, this is often the case with trees introduced from a different country with a longer season. On these foreign trees leaves persist and must be frost killed to be removed. The scars where the pipes of their venation were connected to the twig are still visible on the twig, and in the corresponding scars at the base of the petiole.This casting off of plant parts is called abscission, and trees are masters of it, shedding bud caps, old flowers, leaves, twigs and even large branches.

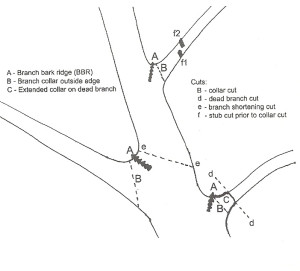

This is a good time to end the pruning season for the birch and maples. Pruned now with yellow leaves or later, they will leak a lot of sap from the wounds in the spring. If we prune these trees when they have green leaves, this leakage does not occur.

The end of September is the best time to do a heavy drenching watering of the ground under the trees to make their passage through winter as safe as possible. We don't want to go too late with this fall drink; if a deep cold spell happened afterwards, damage in branches could occur.

Soon, with all the the leaves' work completed, they will start to fall. Where once so firmly attached by their stem, the petiole, to the twig, they now simply drop. The rainbow leaf show is over and gone; now bare trees stand out against an early winter sky, a really good time to take a close look at your tree's form, hidden all growing season by the leaves.

Dormancy is one of the best times to look for black knots on your mayday, Schubert cherries and chokecherries. A lot of pruning can be done in the dormant season on most trees, except for the birches, maples and walnuts. Dormant pruning is a little tricky and you need to look for three important signs to identify the deadwood. If buds are present on dead branches they will be small, shriveled and dry. Healthy buds with their winter coat like bud caps or scales are plump and full. Dead branches show us two other signs: many times their bark is a different color than the healthy branches, and the last tell-tale sign is wrinkling or shriveling of the bark. As the inner bark has dried up it now shrink fits to the branches and the wrinkles are obvious. Once you master these three signs the door into proper dormancy pruning opens for you. There is little to do after the winter pruning is done. You gave the trees a big drink at the end of September and they are as prepared as possible.

One thing that occasionally shows up during the deep cold spells is the opening of frost cracks. You normally see this only on older trees, but with every aspect of trees and their lives, there are exceptions. What happens is this: live cells can not survive freezing, so they reduce their water content by offloading water into surrounding tissue. The liquid remaining in the cells is much concentrated by this action and thus more capable of dealing with the deep cold, sort of like a stronger concentration of antifreeze in your radiator.

This water, really a sap solution, if close to the outside deep cold begins to freeze and expand. If the cold is deep enough, say -30ish and goes on for long enough, there will be enough expansion that this tension must somehow be released. The trunk pops open, a vertical crack appearing on the trunk. Soon after the cold spell is over, the sides of the crack move back into their original position, and all that is left is the tell-tale vertical scar on the outer bark. On a tree that has experienced this for a number of years, a series of vertical lines in the bark form on either side of the crack, one for each year that the crack opens. In summer the bark, at the edges of the crack that was split open, fuses back together and stays in place until during the next winter's deep cold and the process is repeated.

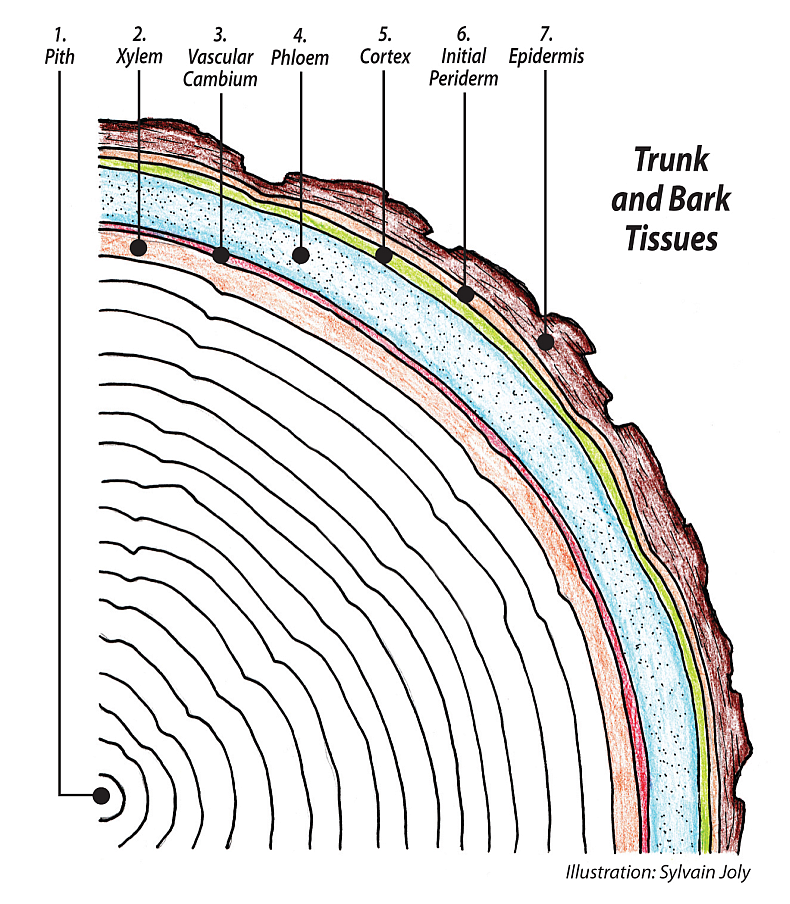

A practice that used to be recommended for winter was the wrapping of the trunk with burlap and other materials. This does nothing to increase the plant's ability to deal with the cold. Cold resistance is genetically determined. What wrapping the trunk does is to inhibit sunlight from reaching the cortex within the bark, which is a photosynthetically active tissue. Any sunny day above 3 or 4 degrees Celsius is a day the tree can produce sugars, food for the winter journey.

Winter watering, although done with the best of intentions, accomplishes nothing. The ground is frozen and the tree cannot take up any water. Water applied to the surface of frozen soil will freeze there and evaporate if any sunny days follow. The same can be said for piling snow under trees; most of it disappears through evaporation.

There is only one thing for your tree to do, hunker down and bear it. A small celebration at the passing of the short day, the equinox, and then wait for the first warm breeze and longer days as spring approaches and another year's work will begin.