Tree work and ideas about trees are haunted by a group of old myths that many times just don't make sense and other times are harmful. This cultural baggage is hard to shake off. It is the sort of folk wisdom uninformed people rely on when doing things on their own without looking for professional help or doing any reading. Anybody can prune a tree, right? Today with the internet, anybody can post anything, and the myths continue. They all stem from a lack of basic botanical knowledge.

The myths I want to address are the right season for pruning, crossing branches, flush cuts, topping, removing 1/3 of the branches of a tree in one pruning job, pruning paint, cavity treatments, and the idea that all the sap is in the roots during winter.

The right season for pruning is something almost everyone has some ideas about. Let me clearly say this, there is no good time to do a bad pruning job, and no bad time to do a good, informed job. But, there are a couple of glaring exceptions. The first is the pruning of birch and maple trees. This should be done only during the summer; otherwise the tree will bleed a lot of sap from the fresh cuts the following spring. The other exception is pruning when the young leaves are forming. This is a crucial weak point in the tree's year and pruning cuts are more vulnerable to disease infection at this time. A favorite time of mine for pruning is late winter/early spring. The tree is still dormant, and without the leaves it is easy to see its structure.

The removal of crossing branches is a common myth. Everybody seems worried about them -- not me. The idea that they are so bad may have come from an area where there are many fungal, bacterial and viral diseases just waiting to pounce on any opening in the bark. Here in the dry west this is just not the case. First off, let's not forget all the good any branch does, crossing or not. To remove a crossing branch for no other reason than theory is to reduce the tree's ability to feed itself. That branch, especially when of some size, contributes a lot of valuable energy to the tree's system. If a crossing branch has become part of the crown and has its own space, leave it. Crossing branch removal theory also ignores the difference in trees' natural densities. To remove every crossing branch from a thick tree like a Mayday would be a serious attack that the tree might not recover from.

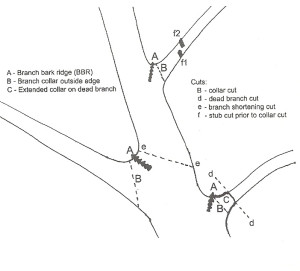

Flush cuts, that is, cuts made that ignore the branch collar, are fortunately becoming a thing of the past. A pruning cut made flush with the trunk, removing the bump at the branch's base, its collar, is one of the most injurious practices done to trees. Removing the collar allows wood-rotting fungus free access into the trunk, while retaining the collar would protect against this infection. The deeper the infection, the greater the energy loss to the tree.The branch collar is a powerful natural protection area and the only time in nature that the collars are removed is when branches are violently broken in storms. Otherwise dead branches are removed at the collar. Inspect any wild or forest trees to see this.

Topping is a ancient practice, still performed, the single most harmful practice done to trees, the worst, usually performed out of fear for the size of a large tree, or from an undisciplined need to control things. The damage inside the trunk is so severe that all of the once healthy, energy storing tissue inside the trunk dies and only the bark is left alive. The tree cut like this has no recourse but to generate multiple shoots from buds stored in the bark for such extreme emergencies. These new shoots literally pop out of the bark and don't have the deep inner trunk attachment that strong, naturally occurring branches do. Twenty years later, these now large trunks have the weakest attachment possible and easily break off when wind or snow loaded. Now you do have a dangerous tree. Topping trees creates more problems for the tree and the owner than any other archaic practice. Don't top; remove, or better yet, let it be.

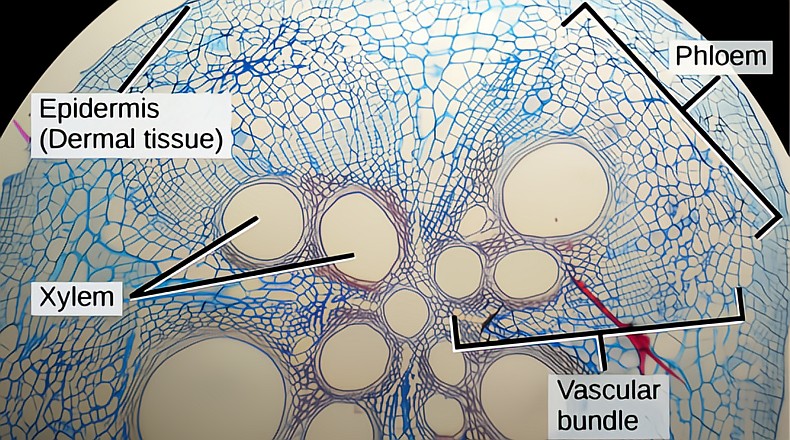

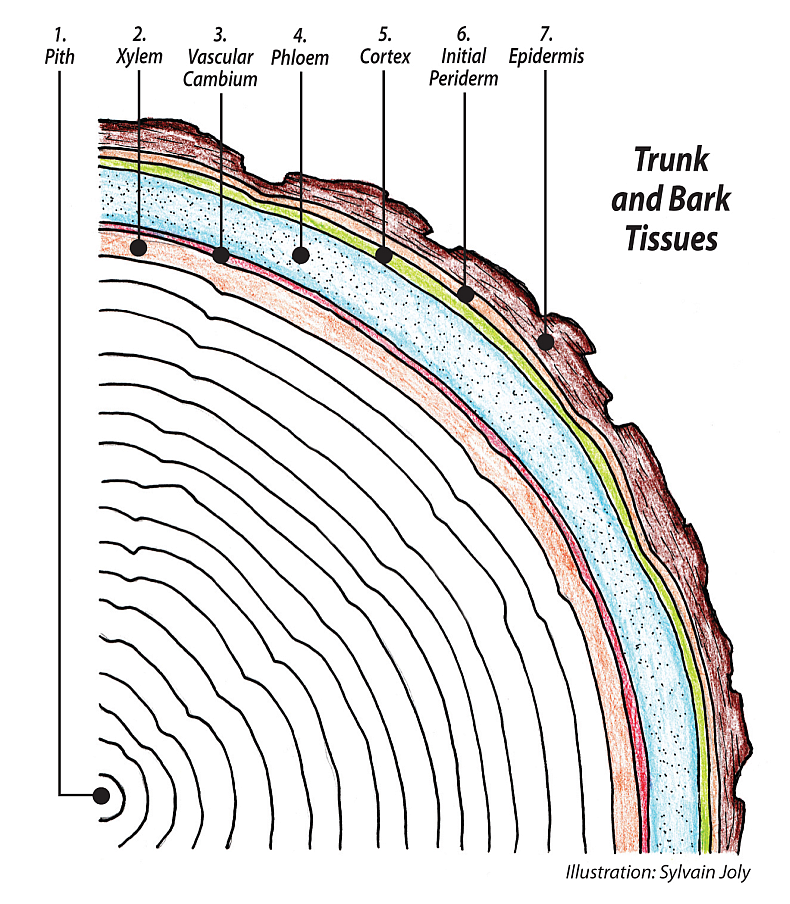

Another deep-seated myth concerns the amount of pruning acceptable at one pruning job. The old rule of thumb said never take more than 1/3 of the branches. How cruel! Seriously, a tree is a balanced integrated living body, just like your own. All the parts of the tree grow in sync, roots, trunk, branches, twigs and leaves. Almost all of the tree's energy comes from its leaves; the rest comes from the cortex, a green tissue under young bark that like leaves is also photosynthetically active, meaning it produces sugar, the only food trees use. The removal of 1/3 of the living branches would be perceived as an emergency, which would produce a large amount of shoot/sucker growth from hidden buds, the tree's attempt to replace a major leaf loss similar to the reaction in a topped tree. There is also a large loss of energy for the tree in having to deal with so many fresh wounds. Show me a neglected tree, years away from its last pruning job, thick, perhaps tangled; a 10% loss of leaf mass would do a tremendous amount to returning the tree to order, without stressing it by over pruning. If you are in understanding with your tree, your pruning will not produce a significant reaction.

Pruning paint is another old story, nowhere near as harmful as topping or heavy pruning, but is still a practice that is much more about people than trees. Trees know exactly what to do when it comes to fresh pruning wounds. They need no substance that we produce to help with their ancient, intelligent "healing" practices. Perhaps this need to doctor comes from the idea that if you get an owey you put a bandaid on it. Mercurochrome was an antiseptic, a red dye used on cuts and scrapes when I was a boy. It didn't do much, but Mom said you were all right and to get back to your playing. Perhaps pruning paint fills the same role.

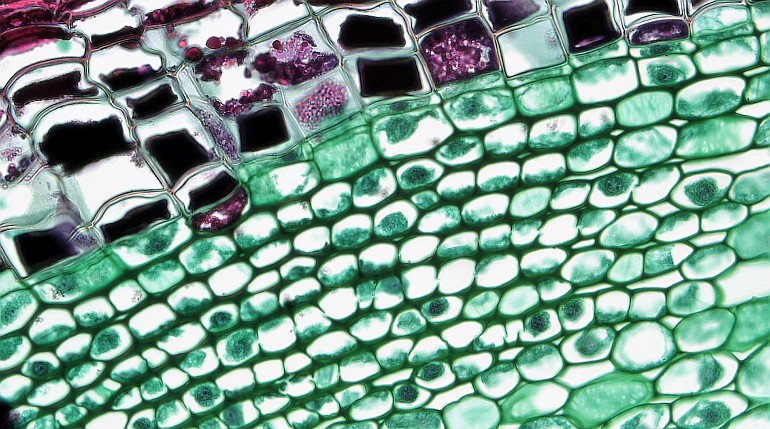

It must have been that some of the first arborists were also dentists, where rot in trees was seen as the same as rot in teeth. The tree has a cavity, we need to remove all the rotten tissue, then we fill the cavity with cement, spray foam or some other substance we believe will do a world of good, all bunk. We may also need to install a drain plug, a pipe from the cavity to the outside of the tree to drain the fluid, more bunk. All of these ideas and practices operate under a mistaken knowledge of how trees really deal with their problems. Animals are regenerators, trees are compartmentalizers, meaning that animals heal their wounds, but trees compartmentalize them, encapsulate them. They do this by building barriers, walls of a sort inside living tissue to keep out fungus and other pathogens. Notice how many cavities hold water; this really means that the cavity is a separate container removed from the actions of sap flow. The cavity is water tight because it is a compartment lined with waterproof, pathogen-proof walls made of phenols and terpenes. When you cut into one of the "walls" you give the pathogen a serious advantage and it can now invade the stored energy of the trunk, until another "wall" is built. What to do with cavities? Leave them alone, nature knows best.

It is common knowledge that the tree's sap is stored in the roots during the winter. But how is that possible? A tree is like a container of water, say one glass of water brim full; how can I compress the top half of the glass into the bottom half? Not possible -- any branch without water or sap is a dead branch. The way to think of this more accurately is looking at sap movement through different seasons. In winter, without the leaves and their heavy water use the movement of fluids in the tree is much reduced. It doesn't stop, the tree still has life processes that require the movement of fluids and energy, but it is reduced from the riot of activity during the growing season.

Tree Care Articles

Debunking Old Tree Myths

- Details

- Written by Kevin R. Lee Kevin R. Lee

- Published: 05 February 2020 05 February 2020

Articles Index

- A Mind Set for Healthy Trees

- A New Tree Care Philosophy

- A Practical Working Model of Your Tree, Part One: Mostly Roots

- A Practical Working Model of Your Tree, Part Three: Leaves

- A Practical Working Model of Your Tree, Part Two: Trunk and Stem

- A weeping apple, some deer, and an arborist

- A Year in the Life of Your Tree - 1

- A Year In the Life of Your Tree - 2

- A Year In the Life of Your Tree - 3

- A Year In the Life of Your Tree - 4

- A Year In the Life of Your Tree - 5

- A Year In the Life of Your Tree - 6

- A Year In the Life of Your Tree - 7

- A Year in the Life of Your Tree - 8

- An arborist thinks on compartmentalization

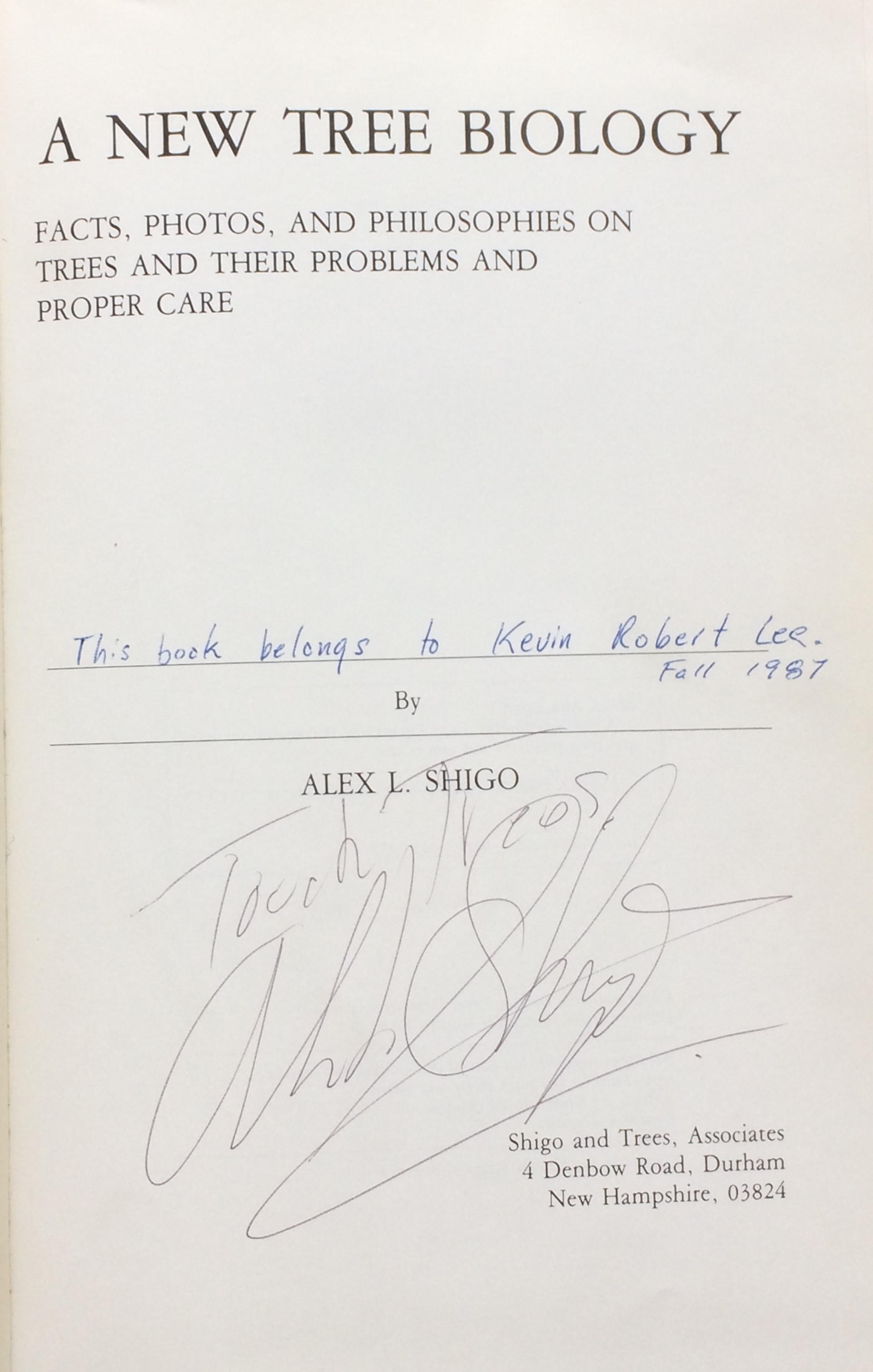

- An Arborist's Education

- Ash Leaf-Cone Roller

- Ash Trees

- Aspens

- Birch

- Botany 1: The whole tree

- Botany 2: What do trees eat?

- Bud Scars

- Burning Bush

- Calgary Soils

- Calgary weather, snow pack, and the drought

- Calgary, from a tree's perspective

- Calgary's Most Dangerous, Dutch Elm Disease

- Calgary's most dangerous: Pseudomonas syringae

- Calgary’s most dangerous: Black knot

- Calgary’s Most Dangerous: Fire blight

- Calgary’s Most Dangerous: The Yellow-Headed Sawfly

- Caragana

- Caring For Your Trees This Winter

- Cell Walls

- Cherry Shrubs

- Cherry Trees

- Conifer Introduction

- Conifer Shrubs

- Conifers

- Cotoneaster

- Cranberries

- Currants

- Debunking Old Tree Myths

- Demystifying Tree Pruning

- Diagnosing Tree Problems

- Diplodia Gall of Poplar

- Dogwoods

- Dr. Alex Shigo

- Eating Apples and Other Hardy Prairie Fruit

- Elders

- Elms

- Epidermis

- Fall Needle Drop of Conifers

- Fertilizer

- Fertilizer 1

- Fertilizer 2: Trees

- First post Feb 23 2018

- Flowering Crabs

- Forsythia

- Fungal afflictions

- Growing Trees in Calgary

- Growing trees in Calgary, hands-on

- Haiku for spring

- Hardiness Zones

- Hawthorns

- Honeysuckles

- How to Have a Successful Tree

- Hydrangea

- In Defence, the Bronze Birch Borer (BBB)

- Introduction to Botany Talks

- Kate's Mayday

- Lack of connection

- Leaves

- Lilacs: French

- Lilacs: Pruning

- Linden

- List of Best Calgary Tree Choices - Evergreens

- Maintaining your pruning tools

- Maples

- Meristems: SAM and RAM

- Mid-Season Gratitude Post

- Mock Orange

- Mountain Ash

- Mugo Pines 1

- Mugo Pines 2

- Mugo Pines 3: Pruning

- My readers, my reasons

- Native Shrubs

- Needle Casts of Spruce

- Ninebark

- Oaks

- Ohio Buckeye

- Old Hacked Apple Trees -- Pruning a Tangle

- Organic Tree Work, Empowering Trees and People.

- Oyster Shell Scale

- Phloem

- Phomopsis Canker of Russian Olive

- Planting 1: Species selection

- Planting 2: Site selection

- Planting 3: Buying your tree

- Planting 4: Root crown identification

- Planting 5, Digging the hole, planting the tree

- Planting 6: Staking

- Planting 7: Watering

- Planting a Tree - Selection

- Planting a Tree - Setting, Staking and Watering

- Polemic and straight talk: the Swedish Columnar Aspen

- Poplars

- Proper Tree Pruning

- Pruning - More Reasons Why

- Pruning in Calgary with Nature in Mind

- Pruning Theory - Tools

- Pruning Theory - Why?

- Pruning tools you need

- Quotes

- Random thoughts from a Calgary Arborist and Tree Surgeon

- Reference books for Arboriculture

- Roots

- Russian Olive

- Septoria Canker on Poplar

- Shrub Introduction

- Shrub Pruning 1 - Theory

- Shrub Pruning 2 - Size Control

- Shrub Pruning 3 - Final

- Shrub Pruning for Size Control

- Shrub Pruning for Size Control 2

- Shrub Pruning Theory

- Slime Flux

- Soils - 1

- Soils - 2

- Spring?

- Stems

- Symptoms of a dry tree

- Symptoms of a sick tree

- The Mountain Ash

- The Three Cell Types

- Thinking of becoming an arborist?

- Toba Hawthorn: Pruning a tangle

- Tree Poem

- Tree Pruning Theory

- Tree Repair

- Tree Repair - 1

- Tree Repair - 2

- Tree Repair - 3

- Tree Repair - 4

- Trees and Their Interactions with Other Organisms

- Two Failures, Griffin Poplar, Manchurian Ash

- Vascular Cambium

- Walnuts

- Watering

- Watering a Birch

- Watering Calgary Trees

- Western Gall Rust of Pines

- What is Tree Whispering?

- When Should a Tree Be Removed?

- White Fly

- White Spruce

- Why is My Tree Dying?

- Willow Redgall sawfly

- Willows

- Wolf Willow

- Woolly Elm Aphid

- Xylem

- Yellow leaves: Chlorosis